Longest Prefix Match (LPM) is the algorithm used in IP networks to forward packets. The algorithm is used to select the one entry in the routing table (for those that know, I really mean the FIB–forwarding information base–here when I say routing table) that best matches the destination address in the IP packet that the router is forwarding. I am an old school systems programmer, used to programming in C or even Python, not the new style method chaining model used in the popular Python data analysis package, Pandas. This post is a description of my experiments in implementing LPM in Pandas. The goal obviously is to ensure that LPM completed as fast as possible on the full Internet feed, but potentially much larger.

Longest Prefix Match

Any IP address consists of two parts: the network part and the host specific part. The network part is also called the subnet. The network part is often written as a combination of 2 pieces: the IP network address and the prefix length. An example of an IP subnet written this way is: 192.168.0.0/24, where the network address is 192.168.0.0 and the prefix length is 24. The prefix length, 24 in this case, represents the number of bits used by the network part of the address. The remaining bits in the IP address is used to construct the host part. IPv4 addresses are 32 bits in length. So, in the IPv4 subnet 192.168.0.0/24, 24 bits are used to represent the network part and the remaining 8 bits are used to assign to hosts. Thus, the subnet 192.168.0.0/24 can contain upto 256 hosts, though in reality, the first and last entries are used up to create a special entry called the subnet broadcast network. So, 192.168.0.1 is the first assignable entry to a host in this subnet. IPv6 behaves the same way except that it has 128 bits instead of IPv4 32 bits.

An IP routing table (I mean, FIB), which a router looks up to decide how to forward a packet, consists of many of these network address entries. The network address entry is also called a prefix because it forms the prefix of an IP address. To select the best matching entry for an IP address, logically, the router must select all the network addresses that can contain the address in question. Thus, if the routing table contains 192.168.0.0/16, 192.168.0.0/24, 192.168.0.0/28, and 192.168.0.1/32, then all of these entries are valid entries for an IP address of 192.168.0.1, while only the first three are valid entries for the address 192.168.0.4, and only the first two are valid entries for the address 192.168.0.20. Once the valid entries are selected, to select only one amongst these, the routing logic selects the entry with the longest prefix. Thus 192.168.0.0/24 is selected over the entry 192.168.0.0/16, 192.168.0.0/28 is selected over 192.168.0.0/24, and the /32 entry wins over all of them for an IPv4 address (a /128 entry in the case of IPv6). Thus, the IP packet forwarding algorithm is called longest prefix match.

Pandas

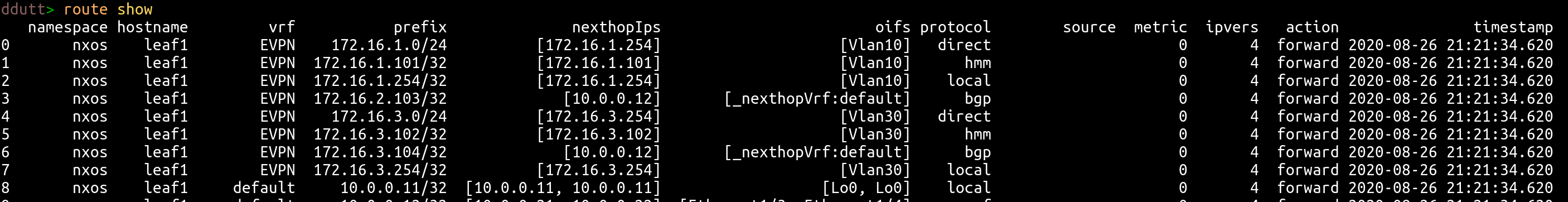

Pandas is is one of the essential libraries for manipulating data in Python. Pandas provides a dizzying number of python functions to implement query and manipulate data. The Dataframe is one of the two most fundamental data structures used in data analysis in pandas (the other being Series). A Dataframe is nothing but a table with rows and columns (every column is a Series). Every column is of a specific data type, such as integer, string, object etc. To those versed in databases, the DataFrame is just like the rows and columns in a traditional Relational Database such as MySQL or Oracle. Thus in Suzieq, the routing table is just a Dataframe. Here is an example of a couple of routing entries as pandas DataFrame in Suzieq

.

.

Figuring out an optimal way of querying and retrieving data can be a fascinating exercise, though many well understood patterns have come about that can be applied to a data analysis problem.

LPM in Pandas

I wanted to implement the LPM logic Suzieq using pandas. A full Internet IPv4 routing table is 800K routes at the time of this writing. This could easily run into millions of entries with multiple routers in Suzieq’s database. So, I wanted an implementation that was fast enough at such large numbers.

LPM in simple pseudocode that is independent of any underlying data structure looks roughly as follows:

selected_entry = None

for each row in the route table

if the given address is a subnet of the prefix

if the prefix length of the prefix is larger than the existing prefix length

selected_entry = row

return selected_entry

Typically the routing table in most packet forwarding software such as the Linux kernel or in software routers is implemented using a Patricia Trie. Lots of papers have explored alternate data structures to implement a faster LPM. Their goal is to forward packets as fast as possible. In packet switching ASICs, the LPM is typically implemented using a TCAM (Ternary CAM). In Suzieq, I’m not forwarding packets, I just need the algorithm to be fast enough to not bore the human using it or be fast enough for other programs to use it.

In Pandas, I have no data structure such as a Patricia Trie. All I have is the Dataframe. I could have tried to suck the data out of Pandas and stuffed it into a Patricia Trie like data structure to query. But this would’ve resulted in too much time to build the Patricia Trie. In addition, in Suzieq its possible to perform the LPM from the point of view of multiple routers in a network in a single query. I needed the ability to support this as well. Constructing multiple Patricia Tries or using a new data structure with modifications to support all the additional requirements seemed too onerous. In any analysis, getting the data into the right structures for analysis consume a significant portion of the time. Caching really helps here, but since the underlying data can change at any time, I wanted to avoid caching the route table in a different data structure. Lots of other possibilities exist, but all involved doing something outside the methods available in Pandas.

To stick with Pandas, the most naive implementation, one that appears most immediately to a programmer schooled in C, is the one that follows the pseudocode shown above. dstaddr is the string containing the IP address I’m trying to find the LPM for.

dstip = ip_network(dstaddr)

result = []

selected_plen = -1

for index, row in route_table.iterrows():

rtentry = ip_network(row['prefix'])

if dstip.subnet_of(rtentry) and rtentry.prefixlen > selected_plen:

result = row

result_df = pd.concat(result)

But this results in a terrible performance, said every thing I’d ever read about programming in Pandas (see this as an example). I had read this enough in multiple places to not even try to implement this to see what the numbers would be. My reading led me to think that the trick had to be to somehow make it a part of pandas natural style of working with data. Maybe implementing IP network as a basic data type in pandas was the right approach.

Pandas allows users to define new extended data types. I chanced upon a library called cyberpandas which made an IP address a basic data type in pandas. I extended this to make IP networks a basic data type in pandas. This resulted in code that looked as follows:

route_df['prefix'] = route_df['prefix'].astype('ipnetwork')

result = route_df[['vrf', 'prefix']] \

.query("prefix.ipnet.supernet_of('{}')".format(dstaddr)) \

.groupby(by=['vrf']) \

.max() \

.dropna() \

.reset_index()

result_df = result.merge(route_df)

The third line elegantly captures the checking if the prefix contains the address, and the fifth picks the entry with the longest prefix length. The same logic as the naive implementation, but this ought to perform better, I hoped. This also provides the LPM per VRF (think of VRF as a logical routing instance, sort of like a VLAN for IP). This model looks more like Pandas data pipeline code ought to look, no iterating with for loops explicitly over the entire route table. This also led to other benefits in basic route filtering and other IP address operations. So, we released Suzieq with this implementation.

It all worked well. Until it ran into the full Internet routing table. Donald Sharp, one of the key maintainers of the open source routing suite, FRR, had Suzieq collect the data from a router receiving the full Internet feed and provided me a copy of this data. This algorithm took close to two and a half minutes to perform the LPM!

Investigating the code, I determined that the time taken was caused by two things: converting 800K prefixes into the IP network data type, and then searching through the entire 800K prefixes to find the longest prefix match. pandas had a different model for iterating over all the rows that was faster than manually iterating over the rows as shown in the pseudo code of the first fragment. That was to use the apply function. This code looked as follows:

route_df['prefixlen'] = int_df.prefix.str.split('/').str[1]

match = route_df.apply(lambda x, dstip: dstip.subnet_of(ip_network(x['prefix'])),

args=(dstip, ), axis=1)

result_df = route_df.loc[match] \

.sort_values('prefixlen', ascending=False) \

.drop_duplicates(['vrf'])

The same logic as the naive code, but more in line with how Pandas best practices recommended. The fifth and sixth lines implement the equivalent of picking the longest prefix entry over all the selected ones. However, this reduced the time window from two and a half minutes to 1 minute 40 seconds. Better, but still way too long.

Python is not known for being particularly fast, but almost no other language has libraries such as pandas for data analysis. So, stuck with python I was. I had read that the trick to the best performance with pandas was to vectorize the operations. By vectorizing an operation, we’d be reducing it to something that another library, numpy, could perform. In our case, we’d have to reduce the longest prefix match to a set of bit operations that numpy could be used for. The longest prefix match can be reduced to:

convert the IP network address to a number

construct the netmask as a number using the prefixlen

if (addr & netmask) == (prefix & netmask)

the address is a subnet of the prefix

In python with pandas, this ended up looking as follows:

intaddr = route_df.prefix.str.split('/').str[0] \

.map(lambda y: int(''.join(['%02x' % int(x)

for x in y.split('.')]), 16))

netmask = route_df.prefixlen \

.map(lambda x: (0xffffffff << (32 - x)) & 0xffffffff)

match = (dstip._ip & netmask) == (intaddr & netmask)

result_df = route_df.loc[match.loc[match].index] \

.sort_values('prefixlen', ascending=False) \

.drop_duplicates(['vrf'])

Essentially, the apply line has been reduced to the first 3 lines in the code fragment above. Even though it looks like intaddr. netmask and match are operating on a single value, they’re actually operating on all the rows of the route table. To someone used to standard programming techniques, this code looks a bit strange. But with this change, LPM was reduced to 2 seconds!

Thus, we systematically reduced the LPM performance from close to 3 minutes to 2s for a full Internet routing table. Doing LPM over 6.5 million rows went from over 6 minutes to 4 seconds!

Lessons Learned

Just for grins and to make this post more complete, I implemented the naive approach to see how well it’d work compared to the other approaches. To make the code produce the same result as the other solutions i.e. produce an LPM result for each host and VRF in a namespace, I modified the naive code to look as follows:

dstip = ip_network('dstaddr')

result = {}

max_plens = defaultdict(int)

for index, row in route_table.iterrows():

rtentry = ip_network(row['prefix'])

if dstip.subnet_of(rtentry):

key = row["vrf"]

if rtentry.prefixlen > max_plens[key]:

result[key] = row

max_plens[key] = rtentry.prefixlen

result_df = pd.concat(list(result.values()), axis=1)

The timing for this was a surprising 1 min and 24 seconds, slightly faster than even the apply method. This surprised me.

I then went ahead and implemented the same logic using itertuples() method of pandas, instead of using iterrows, which is supposed to be faster. It resulted in this code:

dstip = ip_network('dstaddr')

result = {}

max_plens = defaultdict(int)

for row in route_table.itertuples():

rtentry = ip_network(row.prefix)

if dstip.subnet_of(rtentry):

key = row.vrf

if rtentry.prefixlen > max_plens[key]:

result[key] = row

max_plens[key] = rtentry.prefixlen

result_df = pd.DataFrame(list(result.values()))

This was a surprisingly fast 9.76 seconds. Much faster than the apply method, and the next best solution to the vectorized answer. This goes against the grain of accepted wisdom, even if you assume that my attempt to make IP network a native data type in pandas was flawed maybe by my implementation.

“Premature optimization is the root of all evil” is a well-known maxim in software programming circles, a quote attributed to Sir Tony Hoare (the man behind the quicksort algorithm and communication sequential processes among other things). However, I’m also aware of the other famous quote on life by Will Rogers, “There are three kinds of men. The ones that learn by reading. The few who learn by observation. The rest of them have to pee on the electric fence for themselves.” I hoped to have learned by reading, but my observations in this particular case have differed slightly from the popular wisdom. Vectorization is clearly the fastest approach, in agreement with the accepted wisdom around pandas operations. It also is in agreement that itertuples() is faster than iterrows(). However, itertuples() is far faster than the apply() method. Furthermore, from a readability perspective, itertuples is far more readable than the vectorized version or the apply() version.

To summarize the results for the full Internet IPv4 routing table:

- vectorizing the solution: 2s

- using itertuples(): 9.76s

- using iterrows(): 1 min 24s

- using apply(): 1 min 40s

The plan at this point is that the next version of Suzieq will ship with the vectorized version of the LPM for IPv4 and the itertuples version for IPv6, till I can get the vectorized version working for IPv6 as well.

Suzieq

Try out Suzieq, our open source, multivendor tool for network observability and understanding. Suzieq collects operational state in your network and lets you find, validate, and explore your network.